Marijana’s America

By Catherine Kapphahn

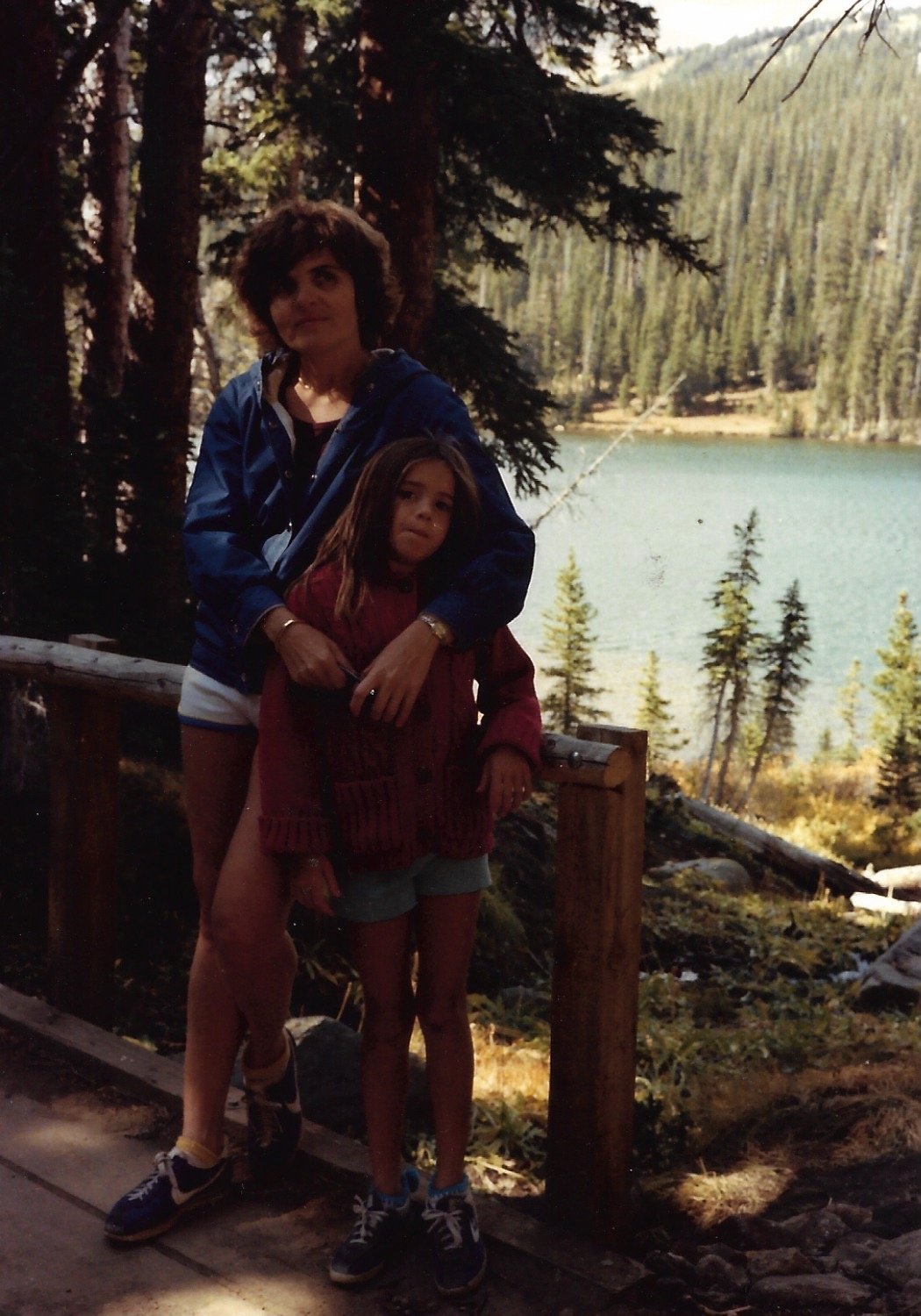

A photo of Catherine and her mother.

She’s an orphaned only child;

I’m her only child.

We’re the only women in this family,

histories sewn together,

countries pulled apart.

She laughs, she loves,

but has no family to share.

“Her accent, it’s so exotic,”

friends constantly point out.

My mom’s from a country no one really knows.

It’s the 80s and it’s called Yugoslavia,

“Is that in Russia?” people ask.

“It’s across from Italy,” I answer,

even though I’ve only been there once.

I don’t even hear her accent,

just when she says mayo-naise.

In this new neighborhood

by the front range mountains

in suburban Colorado,

I have parents who met and

married in South America,

who have lived in Europe,

Asia and the Middle East.

We don’t exactly fit,

our family of three,

but I’m good at pretending

to be more American.

My mom is not good at

pretending to be anyone,

but herself.

“Hey, your mom’s the one always walking through

the neighborhood, right? The one people honk at?”

“That’s the one,” I say, slightly embarrassed

that American men honk their horns at her swinging hips,

and shapely thighs and 80s shorts as she spends hours

walking our neighborhood’s greenbelts.

When people see my mom’s name written out,

they say, “How do you say it? Marijuana?”

“Mari-yana,” I shoot back.

Other Colorado moms don’t wear black leather pants to the grocery,

They don’t suck on a clove of garlic because it’s healthy.

They don’t spend all day making flan for their daughter’s birthday.

They don’t take their daughter to art-house theaters to see François Truffaut films.

They don’t blast Mariachi music while they vacuum with a red bandana tied over their hair.

They don’t say things like: “Look, here’s a good recipe from Sofia Loren in Vogue.”

My mom avoids joining groups; she’s un-involved.

She doesn’t bridge, bake, tennis, PTA, potluck.

She doesn’t join clubs or committees.

She grew up in a communist country,

so it makes her suspicious

of revealing too much;

intimacies can be used against you.

She is distrustful of anyone asking

too many personal questions.

In her country, saying the wrong thing,

even to a family member,

could get you arrested,

sent to a prison island, tortured.

She warns me against the Census.

“Katie, no one needs to know

how many bathrooms we have.”

She has spells of depression,

staying in bed, door closed

for days, weeks, and holidays.

Unprocessed grief, secrets buried deep.

Her parents’ ravaged-lungs;

her parents’ grave.

Wartime whistles

of bombs dropping.

A girl’s running footsteps

to underground shelters.

Men hanging from lampposts

down an empty street.

In darkness, she chokes on grief

for her Baka who she’s abandoned

to escape communism, to seek medical care

and a way out of poverty, hunger

& teenage tuberculosis,

so she travels from Europe,

to South America, to North America

searching for, hoping for,

wishing for, praying for

something to make her well.

None of this does she reveal to me.

Instead she teaches me

you have to walk with your sadness.

Get outside every single day.

Take care of your body.

Take vitamins. Eat healthy.

Dance, move, sing.

She laughs with me as she bounces

up and down, up and down,

on a mini-tramp in the living room.

She watercolors, charcoals,

reads her way back to herself.

There are mornings,

when no matter how she feels

my mom marches up the hill

with her brimmed cap pulled low

and pink legwarmers bunched at her ankles.

In the carpeted basement rec room,

frizzy-haired Marsha leads a crowd of women

in bright leotards, glossy tights and terry cloth shorts.

“Knees up!” she yells, “Heels to butt!”

Marijana, the only Croatian foreigner

in a sea of vacuuming, ironing, dishwashing,

house-wiving, stay-at-home suburban moms.

She jumps, kicks her heels, swings her hips,

circles her arms, hopping from side-to-side,

fists pumping air, clapping with cardio flush,

with American Women.

Nikes pounding to Pat Benatar:

You’re a real tough cookie with a long history

of breaking little hearts like the one in me.

Marijana shouts with the other women:

Hit me with your best shot!

Fire awayyyyyyyyy

My mom shows me that

you have to keep learning bravely.

In her 40s, she sits on the floor

of a dance studio and slips on

pink ballet slippers for the first time,

doing something she has dreamt,

yearned, longed for all her life.

When she stands in first position,

heels together, heart pounding,

about

to embark

on her first plié,

tears of wonder spring to her eyes.

She lifts her hand and places it

tenderly on the wooden barre;

her hand resting

on America.

Catherine Kapphahn is a writer, educator and speaker. Her memoir Immigrant Daughter: Stories You Never Told Me received The Center for Fiction’s Christopher Doheny Award, and Catherine recorded it for Audible. The memoir was also shortlisted for a Del Sol Press Prize. Catherine has received grants from the Queens Council on the Arts and City Artist Corps. Her writing has appeared in Motherwell Magazine, Croatia Week, Newtown Literary, the Feminist Press Anthology This is the Way We Say Goodbye, Astoria Life, and CURE Magazine. Catherine is an adjunct lecturer at City University of New York at Lehman College in the Bronx, where her students’ brave stories continue to inspire her. Catherine also is a yoga teacher. She grew up near the mountains in Colorado and now lives between two bridges in Queens, New York with her husband and two sons. She has also been a guest of Immigrantly, on the episode Unspoken Words.

Disclaimer: The opinions and views expressed in this blog post are those of the writer and do not reflect the opinions or views of Immigrantly.